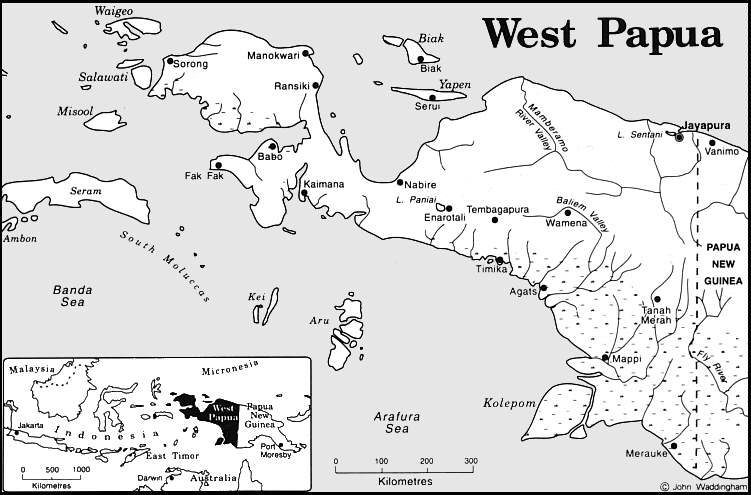

The town of Merauke in West Papua, Indonesia, holds a special place in Indonesian national history. The Dutch sent the first generation of Indonesian nationalists to the Tanah Merah prison camp in Merauke, where some of them died and were buried during the colonial period. Merauke’s mythic stature will make the Indonesian government all the more sensitive to opposition.Land-grabbing is not new in West Papua; it has happened since colonial times (see sidebar). Every acre of Papuan land that has been claimed for a national project was taken by force. In a sense, there is nothing new about the Indonesian government’s latest project, Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE), nor is there anything new about West Papuan resistance.

MIFEE is planned as a series of plantations taking up 1.6 million hectares (6,178 square miles) on the border with Papua New Guinea along West Papua’s south coast. Early last year, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono said MIFEE and similar projects could “feed Indonesia, then feed the world.” MIFEE is expected to provide food crops such as corn, sugar, and rice, as well as feed a growing global demand for biofuels, especially palm oil. The Merauke region was designated a national Special Economic Zone to attract the $8.6 billion investment needed for the project. Large swathes of forests will be cut to make way for MIFEE.

Corporations from the Middle East, Asia, and the United States, as well as Indonesia, are eager to take part. More than 30 companies plan to invest in MIFEE and have received concessions from Jakarta. International Paper, based in Memphis, TN, reportedly has had exploratory talks about building a mill in Merauke or elsewhere in Indonesia. Some companies have begun pilot projects in Merauke.

In West Papua, new “timber mafias” have emerged, linking timber dealers and local security forces with officials. In the past decade, oil palm and pulpwood schemes have started tearing into Papua’s forests in earnest, alongside or in combination with logging. MIFEE represents an additional threat to forests and forest-dwellers. Oil palm projects throughout the country and MIFEE undermine the widely praised commitment of Indonesia’s president to slice 26 percent of Indonesia’s projected greenhouse gas emissions by 2020.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) describes the Trans Fly ecoregion, which straddles the international border of Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, as a “low-lying coastal region of grasslands, savannas, wetlands, and monsoon forest habitats… The area is home to some of the largest and healthiest wetlands in the Asia-Pacific region. It contains landscapes and species found nowhere else in New Guinea.” WWF added that the region is “under immense pressure from development threats.”

Imposed from Outside

Like most of what happens in West Papua, MIFEE was imposed from above. Local governor Barnabas Suebu, who was not consulted before the project was announced, says MIFEE is contrary to his own policy of protecting Papua’s forests. The province’s development plan calls for saving 70 percent of the remaining forest. Suebu has pledged at international forums to increase protected forest areas by 20 percent by ending unsustainable logging and transferring forests to be managed by local communities. TIME magazine named Suebu a “Hero of the Environment” in 2007 for his call for a logging moratorium.

Suebu also worries that MIFEE will threaten millions of dollars in aid by destroying one of the richest sources of carbon credits in Papua. Indonesia has joined the U.N.’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) program, which allows poorer nations to sell carbon offsets to richer ones in return for not destroying their tropical forests. Despite the gover-nor’s opposition, the national government is forcing the provincial government to cooperate with the project.

Many doubt the national government’s ability to oversee such a massive project. Coordination between national ministries has been largely nonexistent so far. In a similar project in Central Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo, companies profited from the timber they cut and never completed the agricultural project that was to replace the forests.

The Forestry Minister was not consulted, either, before MIFEE was announced, even though it will destroy primary forest and the minister has announced plans to plant millions of trees throughout Indonesia. Norway has pledged up to $1 billion to help Indonesia reduce its carbon emissions over the next seven to eight years through the U.N.’s REDD program. The deal with Norway calls for “a two-year suspension on all new concessions for conversion of peat and natural forest.” It is unclear how or if this will affect MIFEE. Indonesia is currently the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Rising Opposition

Customary leaders near the project have rejected it. Indonesia’s main national indigenous peoples’ organization Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN; Indigenous Peoples Alliance of Archipelago) brought concerns about the MIFEE project to the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York on April 29, 2010. AMAN’s statement, endorsed by 26 other indigenous peoples’ organizations from around the world, said, “Indigenous people living in this area depend on hunting and collecting sago as their staple food. This industry will have major impacts on their ivelihoods by changing the ecosystem and threatening Indigenous Peoples’ food sovereignty.”

AMAN warned that the hundreds of thousands of workers needed to work the proposed plantations will overwhelm the local population. About 175,000 currently live in Merauke. West Papua’s total population is only 2.8 million. “These plans will acutely threaten the existence of Indigenous Peoples within these areas, turning them into a minority in number, even leading to extinction in the future. This is, as we may say, structural and systematic genocide,” said AMAN.

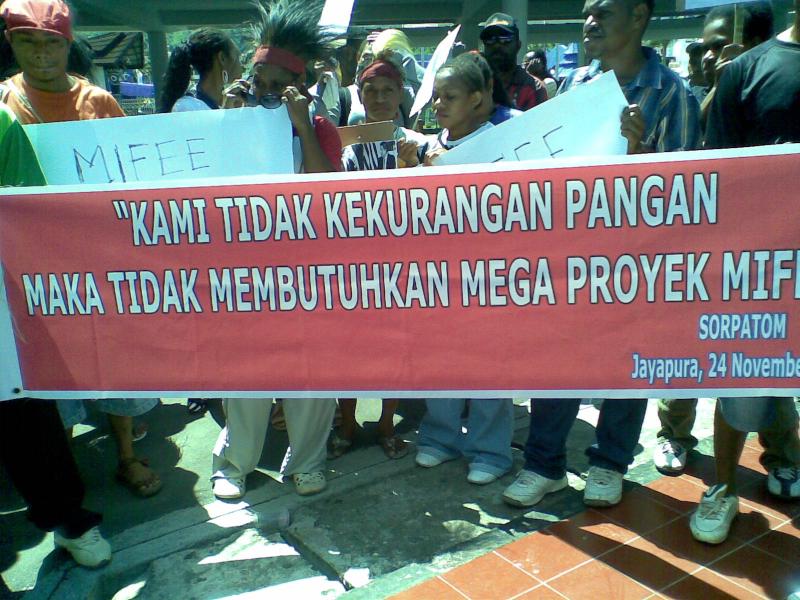

Locally, the Papuan People’s Solidarity to Reject MIFEE (SORPATOM) opposes the project and supports the indigenous groups—Malind, Muyu, Mandobo Mappi, and Auyu—who live near it. SORPATOM has gained the support of national non-governmental organizations. They have held a series of demonstrations in Jayapura, Papua’s capital.

SORPATOM said that MIFEE was already having negative impacts on the local community: “In Kampong Boepe, District Kaptel Merauke district, indigenous communities have started having trouble getting firewood, hunted animals, clean water and their staple food sago. This is because the PT Medco Papua Sustainable Industries…have cleared out the forest and food resources for local communities.” They added that wood processing was polluting their only water source and that sacred places of the Malind-Anim were uncovered in the land clearing process.

Small farmers are opposed because their traditional livelihoods are threatened by the large-scale commercialization of agriculture. “We reject the concept of the food estate. For us, food estates are another kind of land grabbing scheme. It’s like going back to the era of feudalism,” Indonesian Farmers Union official Kartini Samon said. “The regular farmers’ land will be taken by big companies and the farmers will be left with nothing.”

(In)security

Merauke, next to an international border, is one of the most military-dominated regencies in Papua. A 2009 report by Human Rights Watch described how Kopassus Special Forces troops in the town of Merauke “arrest Papuans without legal authority, and beat and mistreat those they take back to their barracks.”The Obama administration announced last year that it planned to resume working with Kopassus after a 12-year suspension because of its past and ongoing human rights violations.

Major projects like MIFEE receive extra attention from Indonesia’s security forces both because they are seen as crucial to the national economy and because corrupt police and soldiers see the potential for profit. Members of the security forces havebeen repeatedly linked to illegal logging throughout Indonesia.At Freeport McMoran’s mine near Timika, West Papua, the U.S.-based company annually reports payments to the police (and in the past, military) for security services. The environmentally devastated mining area has been the site of conflict and attacks on Freeport employees. Some of these attacks, including one in 2002 in which two U.S. schoolteachers were murdered, have been linked to the military or to rivalries between the military and police seeking to justify their large presence and gain greater payments from the company.For West Papuans, MIFEE is yet another unwelcome imposition from Jakarta. Local resources will be seized for the profit of outsiders; Papuans will suffer the consequences. MIFEE is only the latest example of Indonesian plans for Papua that provoke resistance, which fuels repression, which in turn gives rise to greater resistance.

West Papua’s Troubled History

West Papua is the name used by most activists for the western half of the island of New Guinea, which was colonized by the Dutch. It has gone by various names, including West New Guinea, Irian Jaya, and just plain Papua. In 2003, Indonesia divided the then-province of Papua in two, with the larger part remaining Papua and the western end officially changed to West Papua.

Despite sharing its Dutch colonial heritage, West Papua was not included in Indonesia on independence. The Dutch eventually offered West Papuans the opportunity to determine their own political future. But Indonesia began infiltrating troops into the territory, and the United States brokered a deal where the U.N. would endorse an Indonesian takeover. In 1969, the U.N. supervised a farcical “Act of Free Choice”: 1,025 selected Papuans unanimously endorsed integration with Indonesia—many at gunpoint. Most Papuans regard this act as illegitimate and resist Indonesian rule by various means. More than 100,000 Papuans are estimated to have died as a result of Indonesian rule. In addition, the region has been so inundated with migrants that indigenous Papuans are no longer a majority in their own land.

After Indonesia’s U.S.-backed dictator Suharto resigned, East Timor voted for independence in a U.N.-organized referendum in 1999 and the Aceh signed a peace agreement with Jakarta in 2008, leaving West Papua as Indonesia’s remaining major conflict zone. Despite human rights improvements elsewhere in Indonesia, Papuans still suffer at the hands of Indonesia’s security forces—both military and police. Jakarta granted Papua “special autonomy” in 2002, a status rejected as misleading and inadequate in large protests in recent years. Indonesia continues to restrict access to West Papua by journalists, diplomats, and human rights organizations.

In 2003, Yale University’s Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic published a report detailing how Indonesia government has ruled West Papua since the early 1960s. It concluded:

“Since Indonesia gained control of West Papua, the West Papuan people have suffered persistent and horrible abuses at the hands of the government. The Indonesian military and security forces have engaged in widespread violence and extrajudicial killings in West Papua. They have subjected Papuan men and women to acts of torture, disappearance, rape, and sexual violence, thus causing serious bodily and mental harm. Systematic resource exploitation, the destruction of Papuan resources and crops, compulsory (and often uncompensated) labor, transmigration schemes, and forced relocation have caused pervasive environmental harm to the region, undermined traditional subsistence practices, and led to widespread disease, malnutrition, and death among West Papuans. Such acts, taken as a whole, appear to constitute the imposition of conditions of life calculated to bring about the destruction of the West Papuans. Many of these acts, individually and collectively, clearly constitute crimes against humanity under international law.…”