The late 1950s and early ‘60s ban-the-bomb marches between Aldermaston and London during Easter weekends were an inspiration to me. I read about them in the onion-skin copies of Peace News airmailed from London to the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) office in New York.

In 1962 CNVA organized Trident Walks for Nuclear Disarmament, named for three marches from Chicago, Hanover, NH, and Nashville converging on Washington, DC. Because I was in college, I joined the march whenever I could. We started in the spring from Hanover, a college town, and I got maybe a week in. I tried to connect again with the march in May when it passed through New York but was left standing on a corner looking for them as the Armed Forces Day parade, including a Girl Scout troop, passed by. My mother hadn't let me join the Girl Scouts because she said they were too militaristic. Mom was right.

Earlier that year CNVA had organized a sit-down in front of the Atomic Energy Commission office in lower Manhattan. It was the day after my 18th birthday, and my first arrest.

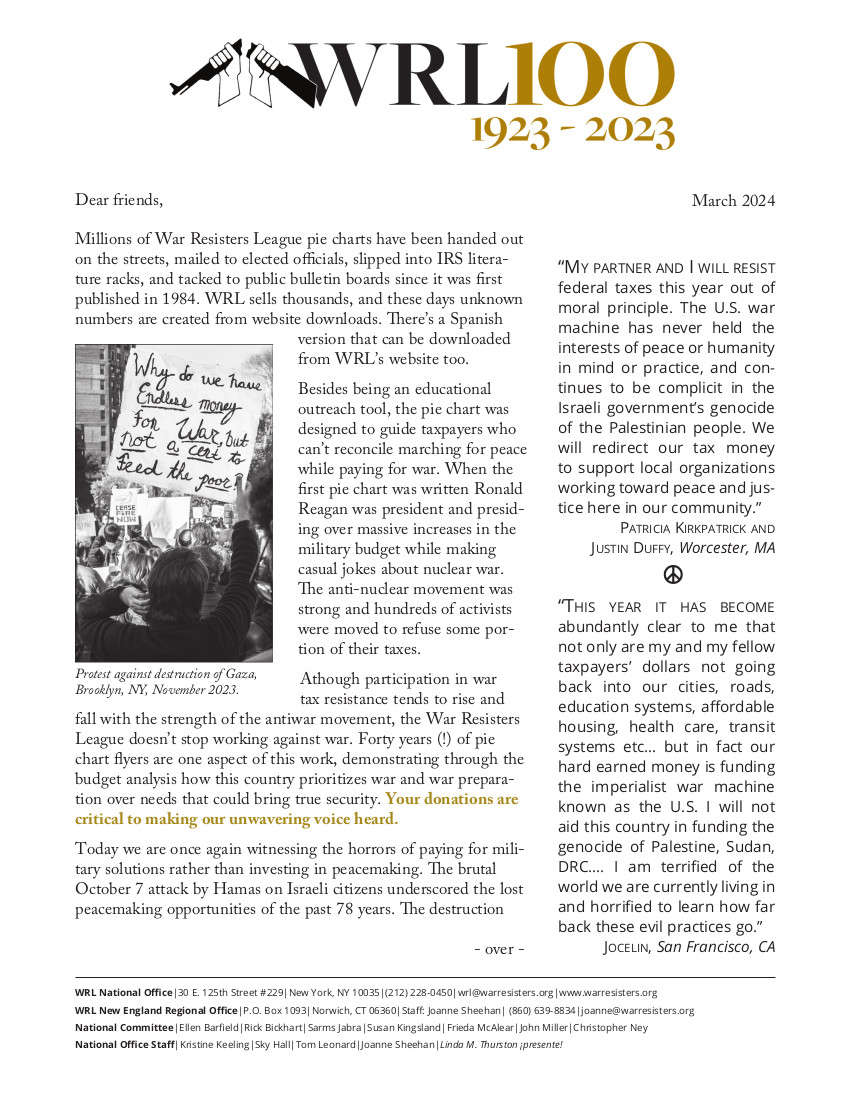

Vicki Rovere (center) during May 8, 1963, General Strike for Peace demonstration at AEC headquarters in lower Manhattan, organized by The Living Theater and War Resisters League. Photo: NYPD

Bonds were forged that day and in the legal planning meetings that followed. Several participants ended up joining a walk. So, when I showed up in Haverford I was reunited with Penny (now Penelope) Young and Peter Giffen, and perhaps some others. The marchers were primarily in their late teens and twenties, although Ken Meister and Joel Kent were in their thirties or forties, and Charles Hornig possibly of retirement age.

That walk had a dress code — no pants for the women or facial hair for the men — trying to avoid triggers for those who might dismiss us out of hand. We walked about 20 miles a day, accompanied by a car that carried sleeping bags and other supplies, and could pick up anyone unable to finish. Plans had been made for feeding and housing, usually with an evening meeting where we spoke to local supporters and anyone else who would come. We spoke about our motivations and experiences and answered questions. At the end of one such event, someone came up to me to appreciate my contribution. They said that instead of sounding canned I had spoken hesitantly and thoughtfully, as if I had been actually considering the question. And throughout my life I've been resistant to preparing sound bites as a result.

Farther along our route we walked in the country, past open fields. Huw Williams kept his eye out for empty soda bottles, which could be redeemed for a nickel. These were glass bottles which would be refilled, not recycled. I wrote a dour poem, "Peace Walks Are for the Birds," which ended, "A flock of pigeons, rising up like doves / Upon the road where lies a robin, crushed."

The next time I could get away, the march was in Delaware. They greeted me with news that a reporter from Esquire had just been there, working on a story about them. Though I had missed my chance to be included, the photographer was due to arrive soon. Soon she did, introducing herself as Diane Arbus. I recognized her name because she and husband Allan Arbus had a photo included in The Family of Man, a treasured book in my own family.

The next day it rained lightly, all day. We pulled on our ponchos and headed out, walking along the side of the road, Diane took photos. The article appeared in the middle of Esquire's November 1962 issue. I was happy to report to friends that I was in an Esquire centerfold (middle person with sign).

Centerspread photo accompanying the November 1, 1962, Esquire article “Doom and Passion along Rt. 45” by Thomas B. Morgan. Photo courtesy of Vicki Rovere.

In these brief visits, I had a rather chaste romance with Peter Giffen, six years my senior. It started when I asked to borrow his nail clipper, an object of fascination for me — my family used manicure scissors. There may have been some foot-rubbing, too. We marchers needed to take care of our mutual mobility.

Then finally, nine weeks out from our starting point, we got to DC and connected with the other two prongs of the trident. We had heard some details of the other marchers — Gene Keyes and Dennis Weeks were two of the Chicagoans. And the Nashville folks, many of whom were based in New York, were a rowdy bunch — Ed Sanders and Nelson Barr, who went on to form the band The Fugs, and some free-spirited women — Jole Carliner is one woman I remember from meetings at the CNVA office.

Oh! There was a poem I had written, which ended

"Sing hey! for the life of a voluntary pauper

With nine people living in a two-room flat.

The way to clear them out is to go on a peace walk

With pot and sex and drinking, and all like that!"