WRL’s 80 Years of Resistance: A Legacy and a Future

By Joanne Sheehan

October 19, 2003

Founded in 1923 to support World War I resisters, the War Resisters League turns 80 this week, making it the country’s oldest secular peace group. For 80 years, it has supported those who have refused to participate in war. On this occasion, especially now as the country turns to a state of permanent war, it’s important to ask ourselves, what’s changed, what hasn’t, and what have we learned?

I joined the League during the Vietnam War because the horrors of that war made me realize that I agreed with the League’s declaration that “war is a crime against humanity.” (We share that conviction, and a pledge not to participate in war of any kind, with other groups in War Resisters’ International in more than 40 countries around the world.) Since then, I’ve been on various League committees and for nearly 20 years have staffed the New England office.

Even before I joined the League, its vision had expanded beyond its original support for conscientious objectors to include resisting the causes of war as well, and that expansion has accelerated in the years since I joined. At the end of World War II, as Black and white war resisters came out of prison and began building what became the civil rights movement, the War Resisters League identified racism as a cause of war. Thirty years ago feminists in the League including myself helped incorporate the stated understanding that patriarchy is also a cause of war. And feminism changed the structure of the League, away from a hierarchical, toward a more participatory decision-making process.

Today I and other counter-recruiters go into high schools with information that provides another perspective for young men and women under the pressure of military recruiters. The League supports a GI Rights Hot Line, which over the last three months has seen a 75 percent increase in calls from women and men questioning their part in the war in Iraq, and a youth program called ROOTS that reaches out to people of color who are particular targets of the military. Thirty-two years ago, on April 15, 1971, I was arrested for the first time at a War Resisters League demonstration at the IRS. Wedged into a doorway with about eight others, I put my body between taxpayers and the agency that collected money for war. I decided I would not pay taxes to pay for war. I, along with many others, still do not pay federal income tax or the phone tax. Now, as then, WRL is organizing a phone tax resistance campaign, encouraging people to “Hang Up on War.”

Thirty years ago I attended nonviolence trainings to practice nonviolence, to better prepare for nonviolent action. In the process I learned the importance of thinking strategically about actions and campaigns. Now I myself am one of many War Resisters League nonviolence trainers, working with groups of all ages, facilitating their exploration and practice of nonviolence, training people in nonviolence as they oppose the weapons of war, the School of the Americas, the war against Iraq, and the many-headed Hydra of the “war on terror.”

Yet with all this activity, the terrible cycle of war keeps repeating, leading some to ask, “Have you made any progress in 80 years of resisting war?” But whereas wars seem to have begun 8,000 years ago, and the League only 80, it’s not a surprise that we haven’t ended war yet.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the League’s commitment to nonviolence. We don’t look for the “good” guy and the “bad” guy in a conflict. That dynamic creates a simplistic justification for killing the “bad” guy and thousands of the people who live near him. We seek the truth in community. We believe in the transformative power of nonviolence. We understand that nonviolence is, as Gandhi said, a courageous choice.

More and more, we are discovering and teaching how corporate globalization drives the engine of war, virtually employing the US military to promote their profiteering. Martin Luther King Jr. pointed to the “giant triplets of racism, materialism and militarism,” which, he said, are “incapable of being conquered when machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people.” In the face of endless war we need to think even more seriously about what it means to “remove the causes of war.”

How do we strategically weaken those causes? Gandhi and King, and scores of nonviolent campaigns throughout the world, give us models and inspiration for how nonviolence can overcome violence, domination, and oppression. Gandhian nonviolence, developed to face an empire, focused not so much on protest but on noncooperation and on a constructive program to “build a new society in the shell of the old.” Gandhi was a nonviolent philosopher who was also a political strategist. Even recently, we have seen how massive nonviolent noncooperation has altered systems and abolished dictatorships that many thought were impossible to change. In our own time, we have to engage in more strategic planning for removal of the causes of war if we want to put an end to war.

A generation ago, King proclaimed, “We still have a choice today; nonviolent coexistence or violent co-annihilation.” We who have made that choice today need to be even more focused and creative. I often quote Barbara Deming, feminist author and activist, to whom I was introduced through the War Resisters League. Barbara’s words give us hope and direction: “Nonviolence is an exploration, one that has just begun.” That exploration is what War Resisters League, and the many others who want to end war, must commit ourselves to for the future.

Joanne Sheehan is the Chair of War Resisters’ International and the staffperson for War Resisters League New England.

Topics:

- Nonviolence

- |

- WRL History

Resource Type:

- WRL History

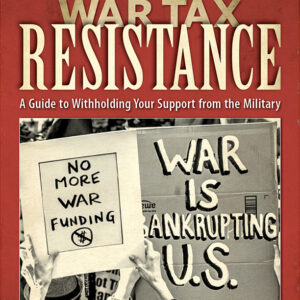

War Tax Resistance: A Guide To Withholding Your Support from the Military

War Tax Resistance: A Guide To Withholding Your Support from the Military