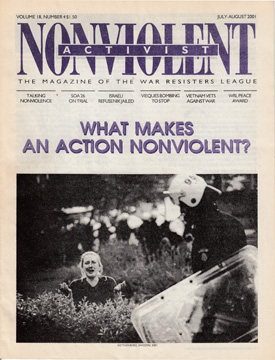

Still Relevant: What Makes an Action Nonviolent? My Favorite Issue: July-August 2001

The July-August 2001 Nonviolent Activist asked “What makes an action nonviolent?” The question had acquired urgency among peace and justice activists in the wake of the November 1999 massive protests in Seattle against the World Trade Organization. I picked this issue to review because Iíd wished that discussion had gone on longer and gotten deeper, and because we are once again in a time of protest with a considerable urgency.

This time, in the wake of the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, “Black Lives Matter” has become the rallying cry of a Black-led grassroots movement. This time the discussion is not about property destruction, as it was 14 years ago, after Seattle, but about the appropriate and effective response to violence committed by official or quasi-official forces. And if the question is still, “What makes an action nonviolent?” we need to explore what we mean by that in this context. How does WRL, which holds that change happens through the implementation of revolutionary nonviolence, and that those most affected need to be at the center of change efforts, engage in this movement?

Let me begin with the definition that nonviolent action is an empowering way of engaging in conflict, an active form of resistance to systems of violence and oppression that is committed to not destroying other people. We need to explore how that is different from actions that are “not violent.” What is the difference between nonviolent direct action and other direct action in terms of strategy and tactics?

We also need to be conscious of the historic context. In the 1950s and early ’60s, the single largest group of people practicing nonviolent direct action were Black people protesting Southern segregation with their bodies. By the time of the 1980s actions against nuclear power and weapons, and by the time of Seattle, that was history. Most nonviolent civil resisters, including the vast majority of the Seattle protesters, were white. In the past few years, that has been changing again, as immigration rights activists and low-wage workers, many of them people of color, have been engaging in sit-ins and walk-outs. And since Ferguson, as the shift in the demographics of protests has become swifter, so, necessarily, have the dynamics of protest and the stakes involved.

This article is therefore an attempt to look both at how the NVA examined the question of nonviolent action after Seattle, especially in its July-August 2001 issue, and how we might examine that question now, in 2015.

There were discussions on nonviolence and property destruction during the Seattle protests, and in the NVA immediately afterward, in the January-February 2000 issue. The headline on the cover was, “Nonviolence at the turn of the century, Showdown in Seattle.” Inside, an editorial said, “On the opening day of the WTO meeting, tens of thousands of environmental, labor, human rights, and religious activists joyously and nonviolently blockaded the meeting site, while some 40,000 U.S. labor union members attended a city-licensed anti-WTO march and rally; during the same day, a small band of protesters who rejected nonviolence rampaged through the street near the meeting site, breaking windows and damaging property.”

In the next issue after “Showdown in Seattle,” a member of one of WRL’s YouthPeace groups objected to the suggestion that property destruction was a rejection of nonviolence. “[N]onviolence means not engaging in harmful acts toward living beings,” he wrote. “The anarchist black bloc that engaged in property destruction only targeted the property of multinational corporations and made sure not to harm individuals.”

The discussion continued in many circles, including the NVA. In the May-June 2001 issue, in “Microcosm of a Changing Movement,” student-activist Lelia Spears wrote about the National Conference on Organized Resistance, “In the movement, as well as at the conference, there is now a move towards acceptance of nonviolence as a tactic among other tactics. Although many see this as a positive move, people new to the movement may be not getting a background in nonviolence, which most agree is useful at least as a tool, a tactic and a strategy.” That article provoked more letters challenging the acceptance of a “diversity of tactics” that includes property destruction.

THE 2001 NONVIOLENCE SPECTRUM

It was in that context the July-August 2001 NVA asked nine activists (including me) to respond to the question “What makes an action nonviolent?” And as I reflect on the nine responses, I see the respondents standing all over the place on the cross-spectrums of what is nonviolence and violence and what is effective and not effective, another issue raised by several of them. (We use cross-spectrums in a nonviolence training exercise – participants place themselves on a grid formed by two perpendicular axes representing polar opposites, in this case, nonviolence/violence and effective/not effective. For more on the exercise, see Spectrum and cross spectrum on the WRI website.)

Activist-poet-priest Dan Berrigan wrote that the main discussions in planning both the draft board raids of the ’70s and Plowshares symbolic disarmament actions consisted of spiritual preparation and the search for symbols. “So wanton thoughtlessness and mere destruction were out, from throwing trashcans to throwing bombs,” he wrote, but “[t]he use of homemade napalm on draft cards and the pouring of blood on nuclear warheads seemed to speak to people.”

“I would rather not focus on whether one form of property destruction or another is violent,” wrote Melissa Jameson, then the director of the WRL National Office, “but on why we do what we do, and how we get there from here. Since one of the tenets of nonviolence is at least the recognition of the humanity of one’s opponent or oppressor, actions that do not allow that, for me, would not be a way I would choose to express myself. If nonviolence means without injury, then nonviolent action would have to mean things that do not bring harm to another living being.”

Anarchist Kadd Stephens wrote that this discussion of property destruction too often leads to the “the crusade for the rights of property,” as he sees it. “Nike’s right to an immaculate storefront takes priority over the tens of thousands of workers exploited beyond the reaches of our imaginations within their factories… This is not to suggest that targeting property is a universally viable or even preferable target… [It] often serves to alienate sectors of the population critical to the success of any movement.”

Mandy Carter, who was on the staff of WRL/West in the 1960s, wrote, “During a ‘Stop the Draft Week’ in Oakland, some protesters turned over cars, slashed tires and committed other acts of physical destruction. They never stayed around to be accountable for their actions… [But] the folks doing nonviolent civil disobedience were accountable… I am very grateful that the first two groups I got involved in were the American Friends Service Committee and the War Resisters League. Both are longtime, pacifist-based national/international organizations. They gave me the philosophical underpinning that has stayed with me for the past 32 years and counting.”

Lelia Spears ended her response by saying “I accept the destruction of property as a tool in an activist’s toolbox, but because I personally do not consider it the most communicative tactic I feel it should be reserved for times when all other means of expression have been exhausted.”

In her earlier article Spears had acknowledged that while any activists were embracing “diverse tactics,” new activists were not getting the training in nonviolent action needed for what she agreed was a useful tool, tactic, and strategy. Unless we have those “other means” in our activist toolbox, we can’t effectively use them. This discussion might have become deeper and more fruitful if it had been able to continue, but it was derailed after September 11 of that year.

Plowshares activist Sachio Ko-Yin, who served more than two years in prison for hammering and pouring blood on a missile silo, asserted his “respect for the Black Bloc participants” and their “sincere desire to end the corporate globalization!” Yet he wrote of their actions, “When several people destroy property in a frenzy (and my impression is that some Black Bloc actions have been frenzied)… I would call it rioting… But because it is so challenging to a property-conscious society, our emphasis on nonviolence and non-hatred has to be so much stronger,… out of reflection rather than rage.”

Yes – what about the rage, the anger about injustice? There is a distance between the activists and the injustice we were/are protesting. This was not a discussion by people who felt a direct impact. Surprisingly, there was no mention of race, and I was the only one who raised the need to look at gender issues, even though the writers were gender diverse. No one mentioned that people of color are already targets of the police and therefore may not want to engage in property destruction or civil disobedience that could subject them to more abuse by the police and courts.

THE SPECTRUM IN 2015

Fast forward to the present day. In the wake of the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, a new movement has risen up, led by those most affected, those whose lives are threatened. African-Americans are organizing local groups around the country. Studies such as “Operation Ghetto Storm,” conducted by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, which shows that a Black man, woman or child is killed by police or vigilantes every 28 hours, expose the perpetual war on the Black population.

As described in the last issue of WIN, Black activists and their allies have organized highway blockades and occupied shopping centers. Groups including the Blackout Collective have shut down public transportation. Black Lives Matter, Asians 4 Black Lives, and white allies shut down the Oakland Police Headquarters. Black Brunch teams go into restaurants crowded with primarily white customers reciting the names of Black people killed by police. Through these actions they are speaking to both the police and the society, forcing them to confront the issue. They are doing what Martin Luther King, Jr. described as the goal of nonviolent direct action in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”: They are “dramatiz[ing] the issue so that it can no longer be ignored.” Some identify their actions as “nonviolent”; others say only “direct action.” None have promoted destruction of property.

In “Turn Up: 21st-Century Black Millennials Are Bringing Direct Action Back,” Malkia A. Cyril wrote in the Huffington Post, “This amazing display of strategic coordination and tactical discipline represents a new era of social protest methodology that seeks cultural as well as political and economic change.” Cyril reminded us that, “The tradition of Black nonviolent direct action in the Americas isn’t new. From enslaved Africans to Black labor activism, Black communities have long used tactics of nonviolent confrontation and non-cooperation to resist extreme repression, expand political imagination and point the way toward a long-term vision for change.”

As #Black Lives Matter proclaims “This is Not a Moment, but a Movement.” Demands have been formulated, strategies developed, trainings held. Creative actions are being organized. Allies are engaging in nonviolent actions around the country. For example, last December students at more than 70 medical schools around the country held die-ins to spotlight racial bias as a public health issue.

What should WRL be doing now? With our history of revolutionary nonviolence, resources on nonviolent actions and nonviolence trainings, our international network of nonviolent activists, and campaigns such as Demilitarize Health & Security, WRL has an important role to play. An organization consisting of primarily white members, we have developed resources on being good allies and are fostering a deeper understanding of gender and racial justice. It is our obligation to keep offering our resources through a diverse groups of activists, organizers, and trainers to a diverse group of activists, organizers, and trainers.

We should not judge those who, for many reasons, do not embrace the term “nonviolent.” But we should not shy away from the use of the word. We must continue our exploration of the power of nonviolent actions, campaigns and movements. We must engage in this movement for racial justice. We are now witnessing empowering ways of engaging in conflict, resisting systems of violence and oppression, resisting the destruction of people without harming the perpetrators. That is what makes an action nonviolent and has the potential for revolutionary social change.

Joanne Sheehan, nonviolence trainer and WRL New England staffperson, encourages people to see War Resisters’ Internationalís Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns for more on pragmatic dimensions of nonviolent action, campaign development, organizing effective actions and training exercises. The book is available on WRL’s online store and can be read online on WRI’s website.