One Year Later: The Republic Windows Story

A year has passed since what Illinois Congressmember Luis Gutierrez described as “a Chicago Christmas Carol”: the factory occupation by 250 workers at Republic Windows and Doors on Goose Island in the Chicago River, an action that captured international attention and provided a stirring victory for workers during a season otherwise characterized by economic pain, turmoil, and tragedy.

The struggle hinged on the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America’s (UE) assertion that because the factory’s main creditor, Bank of America, had received billions in taxpayer bailout funds, it had a responsibility to extend credit to preserve jobs like those at Republic Windows. The union and factory owner Richard Gillman were oddly on the same page in claiming that Bank of America “cut off credit” to the company. The bank’s decision not to extend more credit was understandable given that Republic Windows was obviously failing and (as would later be alleged) was being intentionally looted.

But the struggle became about larger themes than the financial situation of the company. People nationwide were furious at the banks and terrified of finding themselves in the same position as Republic Windows employees, so they lined up literally and figuratively behind the workers.

After a six-day peaceful occupation, which garnered widespread political and community support, Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase agreed to put up $1.75 million to pay the workers the severance and accrued vacation pay they were owed. The union launched a trust fund with the hope of keeping the factory open as some kind of worker-owned cooperative.

Though the idea gained considerable support and attention, the union decided to accept a more promising offer from Serious Materials, a California-based manufacturer of green building products. After difficult negotiations with major creditor Bank of America, Serious Materials made the purchase and signed a contract with the union promising to respect seniority and other aspects of their previous contract. Serious Materials hoped to hire back the full work force by summer.

During the occupation, then President-elect Barack Obama spoke in support of the workers. Since the purchase, Serious Materials has been held up by the Obama administration as something of a poster child for green jobs and the promise of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which includes about $5 billion for various weatherization programs, some of which will go to the highly energy-efficient windows made by Serious Materials. In March, Vice President Joe Biden visited Serious Materials Chicago (previously Republic Windows), and Serious Materials board member Paul Holland introduced Obama at a spring White House briefing on green technology.

The Quad Cities and Wells Fargo

Meanwhile, factories kept closing and the economy kept hemorrhaging jobs, even as the stimulus act went into effect. Unions and workers generally energized and inspired by the Republic Windows struggle looked for ways to use those tactics or at least that spirit in other situations.

The UE launched a very similar campaign against a company called Quad City Die Casting (QCDC), about a three-hour drive from Chicago. Approximately 100 long-time skilled workers, including a diverse group of immigrants and refugees, stood to lose their jobs at the machine parts manufacturer.

The Quad Cities, a solid blue-collar metropolitan area straddling the Mississippi River in Illinois and Iowa, anchored by John Deere and other factories, had suffered many job losses in the economic crisis. Union leaders argued that, though hard hit by the crisis, QCDC had a loyal customer base and orders were bound to pick up with the economy in coming months or years. So, they requested that major creditor Wells Fargo hold off on liquidating the company until a buyer could be found willing to ride out the hard times and keep it open. As they had with Bank of America, the union argued that a bank that had received billions in taxpayer dollars had a responsibility to the U.S. public to help protect U.S. jobs.

This struggle became the linchpin of a larger campaign, spearheaded by Jobs with Justice and the unions, targeting Wells Fargo nationwide. The bank, criticized by the Treasury for being slow to pay back bailout funds, is being sued by the city of Baltimore and the state of Illinois for allegedly steering African-American homebuyers to subprime loans.

In a number of cases, including QCDC, the bank was blamed for facilitating the liquidation of companies that could otherwise perhaps have hung on. For example, Wells Fargo was the major creditor of Hartmarx Corp., a men’s fine clothing company that made Obama’s inaugural suit. Wells Fargo planned to liquidate the flailing company at a cost of 4,000 jobs at several factories nationwide. About 1,000 members of the Workers United union at Hartmarx’s Chicago suburban factory voted to occupy the factory in the case of an impending closure, and Illinois politicians demanded Wells Fargo sell to a buyer who would keep the company open.

Wells Fargo eventually negotiated a sale to a British-American conglomerate that planned to keep the factories open. It was celebrated as a major victory; however, last summer it was announced that the buyer would close at least one Hartmarx factory because of unforeseen financial problems obscured by Hartmarx management.

Back at Quad City Die Casting, UE members hoped civil disobedience would capture public support and imagination as it had at Republic Windows. But the perfect storm of factors—including a large, union-friendly city, a cold winter right before Christmas, and a wave of rage at bailed-out banks—didn’t coalesce in the same way, and the union gained notable but not overwhelming support for actions like blocking the road in front of Wells Fargo. By September, QCDC had closed, though UE continues to press for pay and benefits it says the workers are owed.

Serious Off to a Slow Start

At Serious Materials Chicago, the reopening and rehiring process has been slower than expected or hoped. As of September, only about 20 former Republic Windows workers had been hired back at Serious Materials. This is in part because stimulus dollars have not hit the ground as quickly as CEO Kevin Surace had anticipated. The delays are largely bureaucratic: Windows have not played a significant role in government-funded weatherization programs in years past. The Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program and other subsidy programs typically use an audit with formulas to determine the most cost-effective weatherization strategy for any given home or building. Insulation and other measures are usually considered much more effective than windows, especially because it is only recently that highly efficient windows like those made by Serious Materials have been available. Most windows on the market are considered R2 to R3 on an industry-wide efficiency scale; Serious Materials makes them up to R11.

Serious Materials has also been stymied by the legacy of former owner Gillman, who in September was arrested on a wide range of charges including money laundering and wire fraud. Prosecutors allege he created shell companies and tried to shift Republic Windows’ assets and business to a window company purchased in his wife’s name in Red Oak, Iowa, leaving Bank of America, the workers, and other creditors saddled with Republic Windows’ millions in debt.

The charges against Gillman reveal he hired a consultant who advised him to get rid of the “militant” union. The Iowa factory was non-union, though it did provide well-paying jobs to local residents. Within weeks of Gillman’s purchase, it also was shut down with little warning.

Gillman was held on $10 million bail, later reduced to $5 million, which he posted. Sources say the prosecution might never have happened if it weren’t for the factory occupation, because workers documented the removal of machinery and prevented Gillman and his associates from destroying computers and records that proved crucial to the state’s case.

Surace said Serious Materials is now cut off from most of the company’s former suppliers and buyers because many were either allegedly part of Gillman’s conspiracy or want nothing more to do with the company. Republic Windows management had also left many machines and computer systems damaged or sabotaged, according to Surace.

But he feels things are looking up. On October 30, the company announced a major contract with the Community and Economic Development Association of Cook County (CEDA), the country’s largest weatherization agency, covering the county including Chicago. And Serious Materials is hoping for contracts from greening initiatives in the works at the Willis (formerly Sears) Tower in Chicago and the Empire State Building.

Meanwhile, in October, unemployment hit its highest point in recent times, at 10.2 percent. Though banks are in the process of repaying the bailout money, most people still feel cast adrift in the throes of the economic crisis, with foreclosures still mounting, unemployment benefits running out, and job cuts still looming.

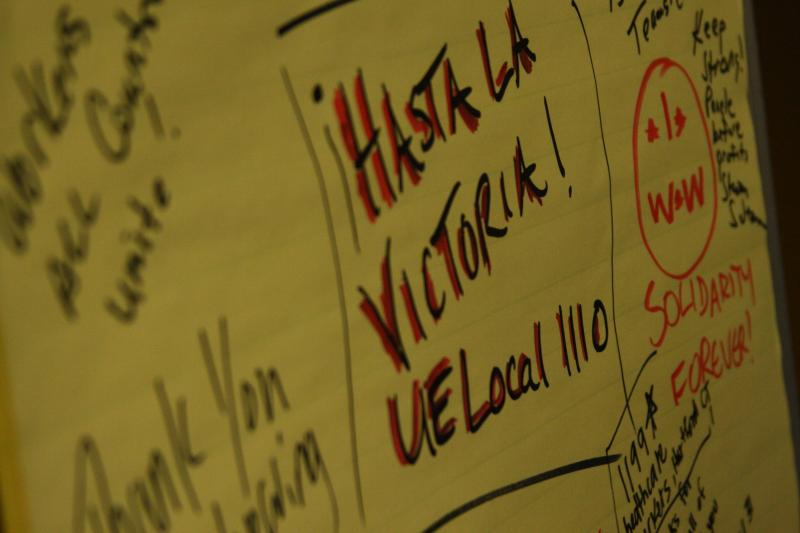

In late October in Chicago, thousands protested during the American Bankers Association annual meeting. UE Local 1110 president Armando Robles, an architect and leader of the factory occupation, ceremonially served pink slips to larger-than-life effigies of Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, JPMorgan Chase CEO James Dimon, and former Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis.

As Congress considers the Employee Free Choice Act that could make it much easier for workers to unionize, supporters of the Republic Windows occupation hope it serves as an ongoing example of how unions can still be relevant and powerful today.

Workers from Republic Windows and Doors have delivered this message as they have toured nationwide discussing their struggle and advising workers in similar situations. They hope their story will resonate not only in the immediate sense but in the labor movement as it moves into the future—a symbol that the glory days of unions need not be a thing of the past and creative, bold, strategic tactics can gain support and success even in a globalized, automated, and now severely stressed world economy.