Southern Intersectional Organizing in the Reagan Era: WRL Southeast

When, in late 1979, Durham, NC-based lesbian feminist organizer Joanne Abel heard about the Klan and Nazi murders of five local leftists at a Greensboro march organized by the Communist Workers Party, she called a friend at the War Resisters League. WRL Southeast office staff organizers Steve Sumerford and Dannia Southerland helped organize a contingent of anti-violence activists to show up in solidarity with the families and larger community grieving the murders. Demonstrators also protested police and government collusion with the Klan and Nazi perpetrators of mass murder, all of whom were eventually acquitted by all-white juries.

Abel remembers the funeral march that she attended with WRL as a deeply politicizing moment, led by a powerful insight: “We’re really all in this together.” She remembers seeing men lining the tops of buildings holding military-grade weapons along the march route, underscoring the danger of the work ahead. Alongside her, War Resisters League Southeast working committee member Faygele ben Miriam, a self-identified radical faerie and dedicated anti-war and gay liberation organizer, wore a t-shirt over his down jacket reading, “Commie, Faggot, Jew,” with a target drawn on his chest. Though Abel had been “toying with separatism” as a lesbian feminist, she remembers acknowledging that the stakes were high and that the political moment called for solidarity rather than separatism.

Sumerford invited Abel to join ben Miriam as a member of the War Resisters League Southeast Working Committee, the group that supported strategy decisions for the southeast regional office. The office was one of WRL’s three regional offices that formed in the late-1970s and 1980s–the other two were based in the San Francisco Bay Area (WRL West) and southeastern Connecticut (WRL New England). While the Southeast office was in regular touch with the national WRL office in New York City, and national WRL organizers marched and organized in the US South, the activities of WRL Southeast often took on a local character, centered in the central Piedmont region of North Carolina.

From its earliest years, WRL Southeast, established in 1977, connected issues in ways that movements would later term as “intersectional,” a term introduced by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989 and adopted before and after that date by leftist social movements following the lead of Black and women-of-color organizing. WRL Southeast embraced a political program that challenged violence in multiple forms. Along with other anti-war groups nationally, it took action to oppose the escalating Cold War nuclear arms race between the US and the USSR and redirect the US military budget to fund human needs. It organized, for example, with the Durham Tenants Steering Committee to fight for government funding for improved housing conditions for poor and working class Durham, North Carolina residents. Additionally, as a regional office of WRL national, a radical pacifist organization aligned with revolutionary nonviolence, WRL Southeast occupied a more radical stance on issues that some in the peace movement feared might alienate the public, such as opposition to nuclear power and direct action against US military intervention in Central America. It organized protests and civil disobedience actions at North Carolina’s massive military bases as the Reagan administration deployed NC-based troops to intervene in Central American democracy. And, beyond what many might have considered the scope of the anti-war left, WRL Southeast organized against violence “at home”: white power vigilanteism, attacks on queer people, and the advance of Christian conservativism and the New Right. One of WRL Southeast’s goals for 1984 was “make racial violence at home a peace issue.”

Members of WRL Southeast saw all forms of violence as deeply interconnected and leveraged national and regional War Resisters League resources to build an intersectional leftist force in the North Carolina Piedmont. Over the course of the 1980s, the WRL Southeast office acted as a hub for local antimilitarist and anti-violence organizing and a growing lesbian and gay rights and liberation movement in North Carolina. As one former WRL Southeast working committee member remembers about the multi-issue, intersectional approach the office took to its strategic planning, WRL Southeast aimed to “build a movement, not an organization.”

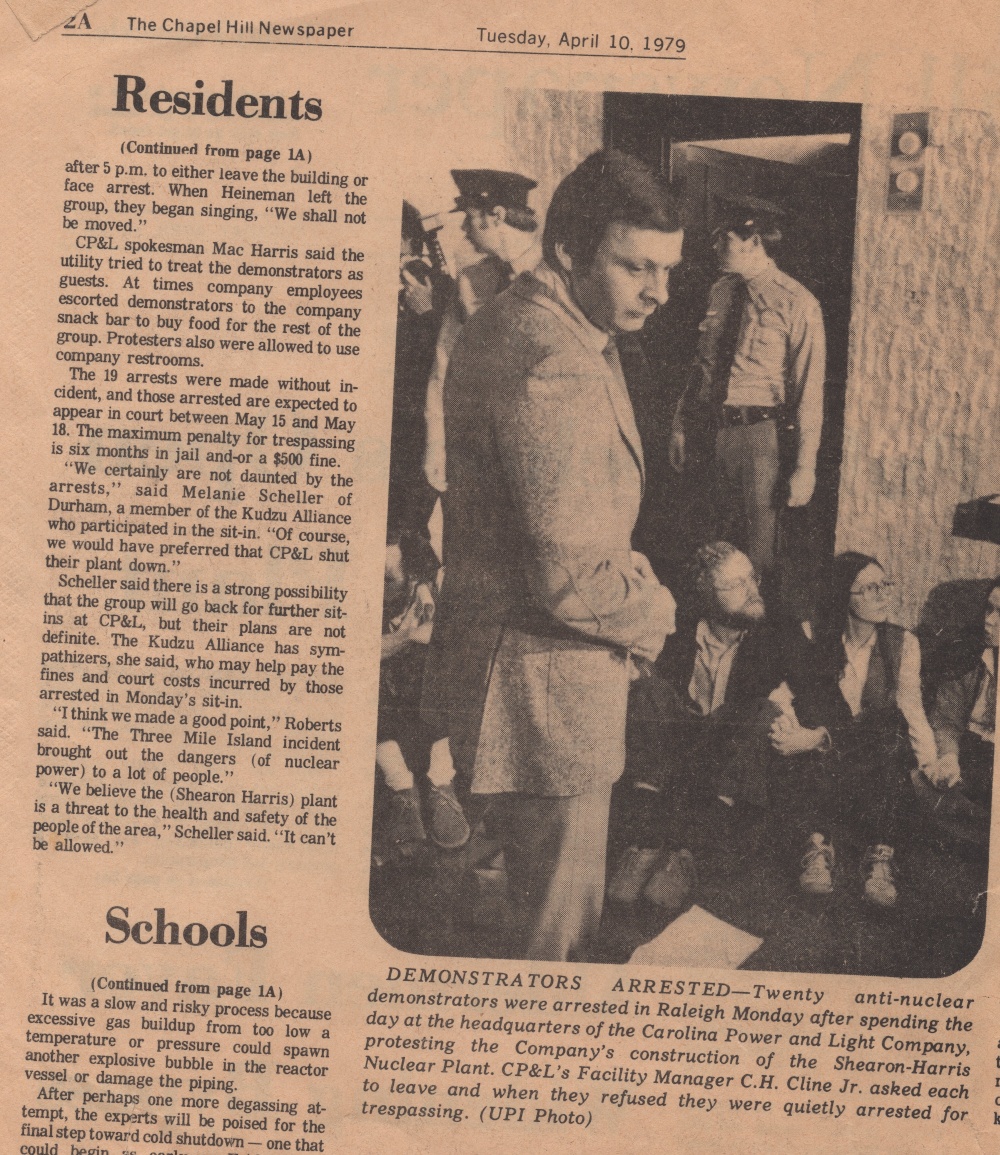

Members of the Kudzu Alliance block an entrance at the headquarters of the Carolina Power and Light Company in April 1979 in protest of the planned construction of the Shearon-Harris nuclear power plant. Some WRL Southeast members met one another through their work with Kudzu. The Kudzu Alliance, and WRL Southeast members as well, took inspiration from feminist-led anti-nuclear groups like the Clamshell Alliance, which shut down the Seabrook nuclear power plant in New England using horizontal, consensus-based group decision making. Feminist group process disrupted top-down leadership structures. (Courtesy Steve Sumerford)

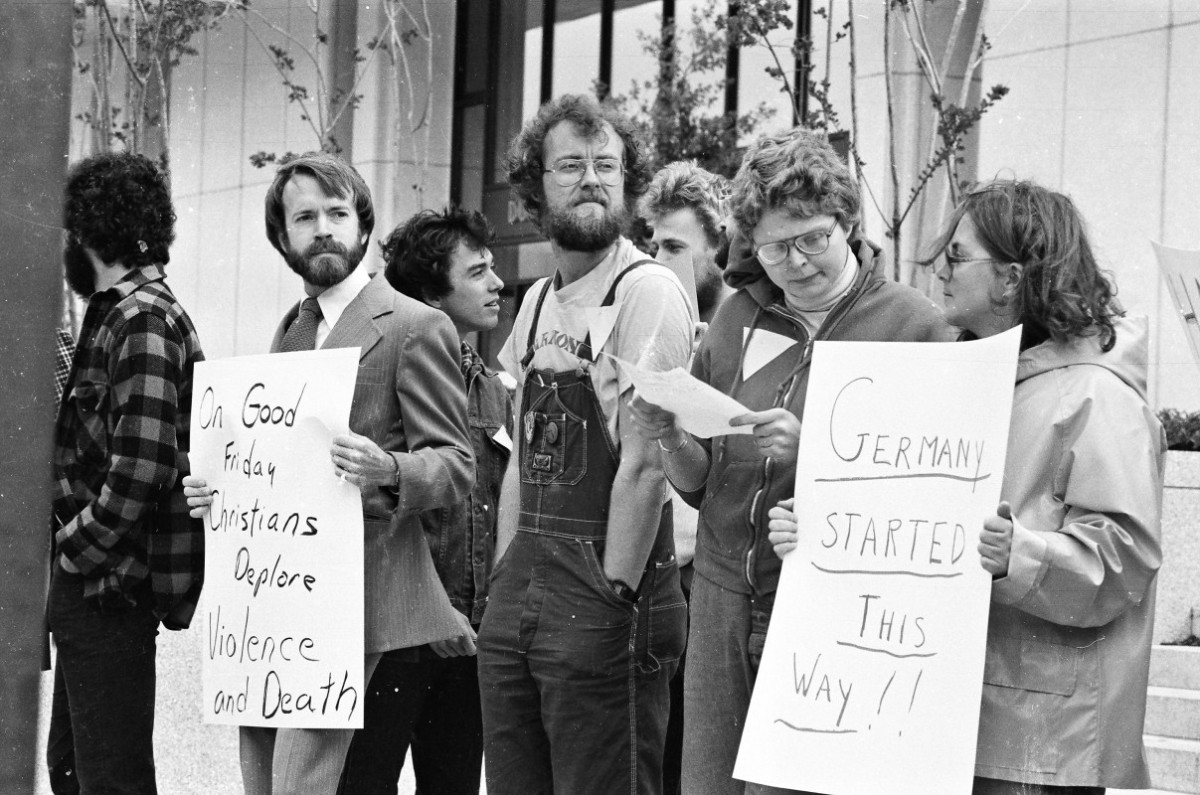

WRL Southeast organizer Steve Sumerford (front row, third from left) with other vigil participants in Durham, North Carolina after the 1981 anti-gay murder of Ronald “Sonny” Antonevich at Little River in north Durham. The killing sparked the organizing for “Our Day Out”–the Triangle’s first lesbian and gay Pride march. Image NCC_0107_0206, Little River beatings protests, Oversize Box 8, Allan Troxler papers, LGBTQ+ Community collection (NCC.0107), North Carolina Collection, Durham County Library, NC.

Participants in the 1977 WRL national conference in Lacey, Washington. This was one of the early WRL national gatherings that connected WRL Southeast office co-founders Diane Spaugh and Steve Sumerford (third row, far right) with future WRL Southeast staff organizer Mandy Carter (third row, sixth from left). Photo by David McReynolds

– blog post by Kimber Heinz

This piece is intended as the first post in a series about WRL Southeast over the course of 2023.

Share