From

War Tax Resistance:

A Guide to Witholding Your Support from the Military

(buy the book from our online store)

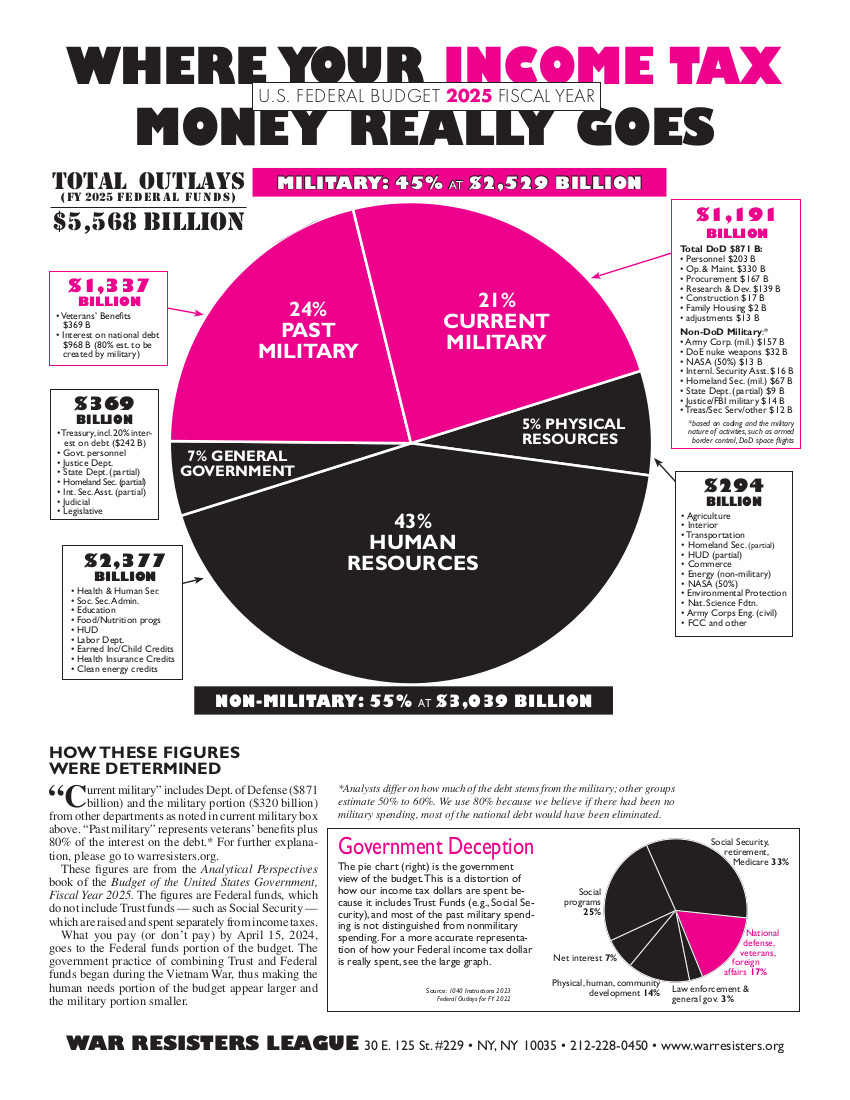

Expenditures for past wars are reflected in veterans’ benefits and interest on the national debt. Veterans’ benefits have been clearly itemized in all budgets since 1789. However, knowing what percentage of the debt results from wars or military spending is not always easy to determine.

During and immediately following every war (and sometimes just before) the national debt rose dramatically, except in the case of the Korean War as noted earlier. Until recently a significant rise in the debt was rare during non-war years (one striking exception was during the Depression when social spending increased rapidly). Historically the national debt has been a by-product of wars. Therefore, interest on that debt as a rule has been an expense of past wars.

For 25 years following the end of World War II (1945-70), the national debt hovered between $250 and $350 billion. Interest on the debt was probably at least 80% war-created. During the Indochina War the debt went into another climb, because the government did not raise sufficient taxes to offset the war expenses. However, following the war the debt continued to rise dramatically (surpassing $1 trillion in fiscal year 1982, climbing to $3.5 trillion in 2002). Part of that was due to inflation, but even after subtracting inflation (see chart on page 19), military spending began climbing in 1977, a climb that rapidly accelerated before peaking in 1989, followed by a slow decline until 1999 when it began to rise once again.

Since the Indochina War ended in 1975, the U.S. has been involved directly in fairly brief interventions (e.g., Panama, Granada, the Gulf War, Somalia, the Balkans). Therefore, the rise in the debt is not primarily war-created, and current interest on the national debt might be as little as 40% to 50% war-created. However, despite this lack of long-term wars in recent years, high military spending (because of the Cold War, the arms race, the “war on terrorism,” and a military establishment seeking to perpetuate itself) has contributed significantly to the debt.

First, however, some decisions need to be made on how to calculate the military portion of the debt. The following example illustrates two possible methodologies. Suppose that for a particular year military spending was $300 billion and total spending was $600 billion, and the deficit for that year was $100 billion. Methodology A: Since military spending was 50% of total spending, you could argue that the military portion of that debt was 50% or $50 billion. Methodology B: Or you could argue that if there were no military spending, there would be no debt – in fact, we would have a surplus; therefore, the debt for that year is entirely military-created.

Using the first methodology, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (Washington, D.C.) calculated that the interest payments in the 1980s on the accumulated national debt should be considered 50% to 60% military and war-created.8 They began their calculations using FY 1940 as the base year, because at that point the accumulated debt was very small compared to current standards. Then each subsequent year the military-created contribution to the deficit of that year (if there was one) was added to the total accumulated military debt. In this way, the military-created portion of the total national debt was calculated.

If methodology B is used, the military-created portion of the national debt would be 100%. This is because in almost every year since 1940 military spending exceeded the increase in the debt, if there was one.

As a compromise WRL has used 80% of the interest on the national debt as being military and war-created.