WIN REVIEW

Israeli General’s Son Becomes One-State Advocate

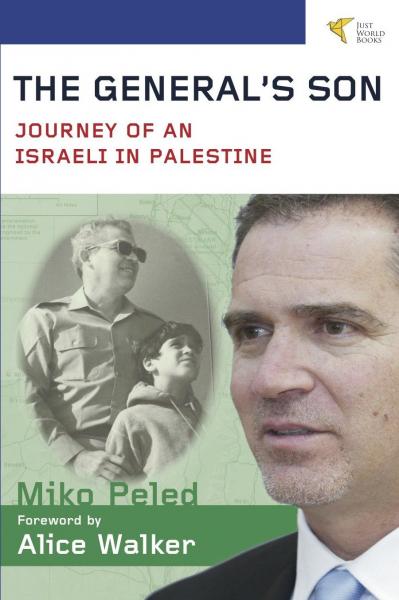

The General’s Son:

The General’s Son:

Journey of an Israeli in Palestine

By Miko Peled

Just World Books;, 2012; 223 pp. $20

An ex-commando with a sixth-degree black belt in karate would seem the least likely person to doubt his physical safety. Yet Miko Peled once feared for his life just asking for directions in an Arab city. In its retelling of such encounters, Peled’s memoir provides an opportunity to peer deeply into the mind of an Israeli Jew on an extraordinary personal journey to shed his people’s prejudice-fueled paranoia and become a visionary peace activist.

With pride and intimate detail, Peled describes family origins that make his evolution even more significant. His grandfather was Zionist spokesman Avraham Katsnelson, an Israeli Declaration of Independence signatory and ambassador. His great-uncle by marriage, Zalman Shazar, served as president of Israel. We also meet his accomplished grandmothers and mother. The latter complicated the simplistic world of Miko’s childhood Zionist worldview by refusing to live in a home taken from Palestinian refugees.

This book is the first memoir to cover in detail the author’s famous father, General Mattityahu (Matti) Peled, a soldier turned scholar and dissident. A man of deep contradictions, the senior Peled “did not usually have conversations with me or my siblings,” Miko writes, attributing this to Matti’s insecurity. Yet Miko “wanted very much to be a hero and a great general” like his father.

The author’s intense admiration of his father may explain one deficit in this important and valuable book: It fails to clarify Gen. Peled’s initial stance on the key strategic and moral question of whether Israel should have created the West Bank and Gaza occupation that he spent his later years decrying.

The author cites former Israeli Prime Minister Moshe Sharett as recounting that in June 1967 the general told the Israeli cabinet “in no uncertain terms that the army is preparing for war ‘in order to complete the conquest of the Land of Israel and to push Israel’s eastern border to its natural location on the banks of the Jordan River.’” Yet the book also states, “When he was pushing for the war, he had imagined that it would be a limited war with Egypt to punish the Egyptians .... Taking the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Golan Heights was never part of any official plan.”

Whatever his expectations of the war, immediately after it Gen. Peled recommended Palestinian statehood and warned that maintaining an occupation would provoke resistance that the army would have to quell. The general cautioned that this would “turn the Jewish state into an increasingly brutal occupying power and eventually a bi-national state.” Retiring from the army, he pursued a path of solidarity. He established the Arabic Literature Department at Tel Aviv University, founded the Israeli Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace, instated an unofficial dialogue with the PLO, and represented an Israeli-Palestinian party in the Knesset.

Miko’s path bears some similarities. After high school, he joined Israel’s Special Forces, earning the coveted red beret, but surrendered that hard-won status as soon as he earned it, becoming a medic. Finally, disgusted by the 1982 Lebanon invasion, he buried his service pin in the dirt.

Miko turned from the conflict to two new loves: Gila, an army medic he would marry, and karate, which he left Israel to pursue. Karate gave him a more moral approach to “understanding violence and the difficulty in defining non-violence, overcoming an opponent that is seemingly impossible to defeat....”

The conflict he left nevertheless found him again in 1997 when Miko’s 13-year-old niece was murdered by Palestinian suicide bombers, creating the Peleds’ own “Black September.” Inspired by his grief-stricken sister and brother-in-law’s dedication to reconciliation, Miko looked for a way to help stop the madness. As Alice Walker writes in the foreward, “There must be people, in all walks of life, who decide: Enough’s enough; there are children here.”

Miko began to participate in the San Diego Jewish-Palestinian Dialogue Group in 2000, notwithstanding Gila’s excessive fears for his safety. The group painfully demythologized the conflict for Peled. He joined with Palestinians to share publicly a joint vision for peace and raised enough money to donate 1280 wheelchairs for needy Israelis and Palestinians.

Yet older fears surfaced. In a 2003 visit to the Palestinian-Israeli city of Nazareth, Miko and Gila realized they needed to ask for directions. “The thought of admitting that we were lost and vulnerable in this seemingly hostile environment seemed tantamount to inviting an assault. In that moment, we became the defenseless Jews that we were brought up to be, just like our forefathers in the ghettos of Eastern Europe.”

In the eight years that followed, Miko journeyed a long way into what must have seemed the heart of darkness. Over-ruling family members’ protests, he took one of his three children to meet Palestinians in Hebron. He confronted Israeli border security and was detained three times by the army. He began to visit the West Bank alone and befriended Palestinians committed to nonviolence, even those who had previously killed Israeli soldiers.

Facing Israeli occupation forces with contempt but not fear, Peled nearly got his thumb broken by an angry soldier. (The author ironically felt less intimidated by the military’s potential for violence than by random Arab pedestrians in Nazareth. This illustrates the biases engendered by the Zionist-fed racism to which he says he was exposed all his life, despite his relatively enlightened upbringing.)

Miko takes a special interest in Gaza, where his father had served as military governor in 1956-57. In 2008, Miko tried unsuccessfully to enter and deliver medical supplies there. The Strip is also the setting for one of the book’s most haunting stories, as an Israeli tells Miko how, during military service, he had drowned Gazan fishermen just “to teach the Arabs who was boss.”

Miko’s love of karate provided him another way to contribute to peace. Instructing Palestinian West Bank children in 2010, he told them that the self-defense method “teaches us to overcome insurmountable obstacles, and you will find a way out of the injustice in which you live, and do it without having to sacrifice your young lives.”

On that same trip, Miko learned what might have caused his father to turn against the establishment. Abu Ali Shahin, a former Palestinian militant leader, revealed to Miko that Gen. Peled had investigated a massacre of Shahin’s entire family in Gaza’s Rafah Refugee Camp after the end of the 1967 war. Miko’s mother confirmed, “Your father was so upset, he couldn’t sleep for weeks. He wrote to Rabin and to Haim Bar-Lev about it, but they did nothing. This changed him completely.”

Miko has gone even further than his father, rejecting Zionism and embracing bi-nationalism as the only just solution still possible: “There is no political will within Israel to give Palestinians their freedom.... By ruling over two nations, Israel has chosen to be a bi-national state. All that remains now is to replace the current system whereby only Israeli Jews enjoy the freedoms and rights of full citizenship with one that will allow Palestinians to enjoy these rights as well.”

Writing of the difficulties caused by his courageous and compassionate activism, the author reveals lost friendships and even family tension. Yet he seems more driven than ever to make a dent in the intractable Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The historian and social psychologist alike will appreciate this book, which serves as an unusually unguarded account of Israelis struggling to understand the truth, overcome their fears, and seek peace. The book deserved more proofreading (e.g., run-on sentences appear throughout), but it engrosses the reader and offers literary charms. (“Every leaf of every tree and shrub seems delighted to feel the sun after a long, cold night.”)

Anyone interested in understanding Israel/Palestine from a personal and historical perspective will want to read this powerful book and look for more from this passionate activist in the years to come.